By Susan Jayne

Natalia Ginzburg’s memoir “Family Sayings” (Lessico Famigliare), first published in 1963, is experiencing a revival among English-speaking readers. This classic work of Italian literature captures the humor, and hardships of a family navigating Fascist Italy before, during, and after World War II.

⸻

Born Natalia Levi in 1916, in Palermo, Ginzburg was the daughter of a Jewish father, Giuseppe Levi, a biology professor from Florence, and a Roman Catholic mother, Lidia, from northern Italy. When Natalia was three, the family moved to Turin, which became the backdrop for much of “Family Sayings.”

The memoir spans the years from 1919 to the postwar, in Italy, with the most passages focusing on the young Natalia, her sister, and three brothers, as they grow up in a household full of strong personalities and sharp wit. Ginzburg describes her family’s clashes with Italian Fascism, including the imprisonment of her father and brothers for their anti-Fascist activities.

⸻

Natalia’s marriage to Leone Ginzburg—a Russian-Italian intellectual and fellow anti-Fascist—was marked by tragedy. Leone died in German captivity, leaving Natalia with three young children. Despite this heartbreak, her writing is never self-pitying. She portrays both joy and suffering with striking clarity and restraint, much like Carlo Levi did in his celebrated memoir “Christ Stopped at Eboli,” which recounts his exile in Basilicata during the 1930s.

⸻

One of the book’s recurring themes is whether the Levi family’s troubles were due to their political stance against Mussolini or simply the quirks of an eccentric family. Ginzburg recounts episodes such as her brother’s arrest for smuggling anti-Fascist literature from Switzerland and her father’s mixed feelings—proud of his son’s courage but furious over his carelessness.

Another brother, serving in the military, went AWOL and risked a court-martial just to go skiing with a young woman. These stories, told with humor and precision, highlight the complexities of resistance, family loyalty, and individual recklessness.

⸻

I wish I had discovered Ginzburg’s memoir earlier. My father, a retired colonel, rarely enjoyed books by women. However, he might have appreciated Ginzburg’s direct, unadorned style. She wrote with a sharpness and grace to transcend gendered literary expectations.

I first encountered “Family Sayings” thanks to Letitia Hardy, an Italian language tutor, who introduced the book to her Italian literature group, in New Orleans, sometime after Hurricane Katrina. We were all captivated by Ginzburg’s language—so simple, yet deeply evocative. Compared to other Italian classics, such as Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa’s “The Leopard” (Il Gattopardo) or Alessandro Manzoni’s “The Betrothed” (I Promessi Sposi), Ginzburg’s prose was refreshingly accessible.

⸻

Ginzburg was briefly a member of the Italian Communist Party before becoming a socialist to later serving in the Italian Parliament. In the 1950s, she and her second husband lived briefly in England, an experience she found dreary. In her essay “La Maison de la Volpe” (The House of the Fox), she criticizes British culture for its gray weather, bland food, and lack of passion—a reflection, perhaps, of her homesickness for Italy.

⸻

I have yet to read Ginzburg’s novels, which are said to be more somber than her essays and memoirs. But with a wave of new English translations underway, now is the perfect time to rediscover her work. My copy of “Family Sayings” is out of print, but a recent translation—Family Lexicon—is considered a more accurate rendering of the original title.

If you’re looking for an unforgettable memoir of Italian family life, World War II history, and the resilience of the human spirit, start with “Family Sayings.” Like me, you may find yourself ordering more of Ginzburg’s books before the summer is over.

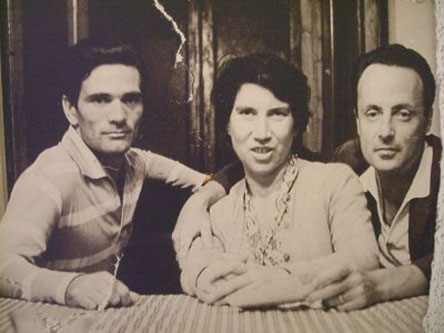

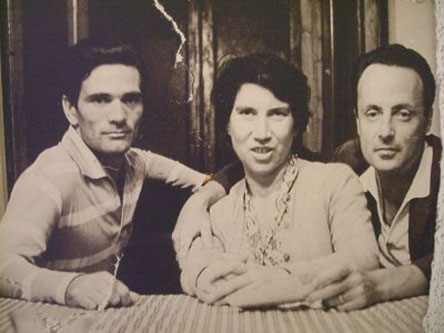

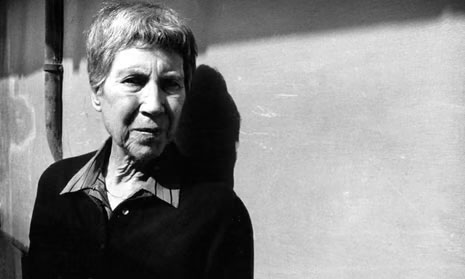

Editor's Note: Natalia Ginzburg is pictured with Pier Paolo Pasolini, filmmaker and poet, and Italo Calvino, writer, on her left. A second photograph shows Ginzburg with her first husband, Leon Ginzburg, a leader in Italy’s anti-fascist movement, who was arrested, tortured and murdered in jail in 1943. Ginzburg was pictured in the late 80s. She died in 1991.