|

||

|

||

|

News Archives - NOVEMBER 2011 The Latest News…from an Italian American Perspective: OH…TO GO BACK TO THE DAYS OF THE LIRA

Italy’s ongoing debt crisis has more than a few Italians longing for the days of the incomparable lira. Before they changed over to the Euro in 2002, Italy used to handle its debt by devaluing its lira currency, inflating prices all over the peninsula, and exporting its way into solvency. Now tied to the Euro, Italy has to face its debt head-on, making tough budgetary choices, not easy to accomplish with the country’s impassioned and diverse political class. Americans who visited Italy were always astounded at the currency exchange with the lira. For instance, in February 2002, just a few months before Italy transferred to the Euro, the currency exchange ratio between the lira and U.S. dollar was 2,236 to 1. Italian lira notes came in denominations of 500,000, 100,000, 50,000, 10,000, 2,000 and 1,000. Often printed in warm colors, the lira often depicted famous Italian inventors, artists and a celebrated educator. Last Exchange Rate between Lire and Dollar(s) According to the U.S. mint, the following amount of lire equaled the amount of dollars in 2002, the last year of Italy’s lira. 2,236 lire = $1 U.S. 11,180 lire = $5 U.S. 44,720 lire = $20 U.S. 223,600 lire = $100 U.S. Although shocking to Americans, currency denominations in the thousands were mostly shrugged off by Italians. In return for high inflation, Italy had economic sovereignty to control debt and grow the economy.

THE END OF BERLUSCONI…NOT SO FAST

Silvio Berlusconi stepped down as Italy’s prime minister November 12 when Umberto Bossi of the Northern League Party joined a growing chorus of no confidence. Berlusconi needed Bossi to keep his frail coalition together in parliament. When he failed to control Italy’s spiraling debt, he lost Bossi and other supporters. The debt crisis has dogged Berlusconi for over a year. He tried to buy time by brokering an austerity plan in the summer. The effort was little more than window dressing with hopes that Italy’s economy could turn around and diminish the crisis. When that did not happen Berlusconi had to broker an agreement between rivaling parties. He had to solve the problem with an austerity plan to cut sizeable chunks of government; almost impossible in Italy’s current political state. Unable to get the job done, Berlusconi had no choice but to step down. Berlusconi’s departure was met outside parliament with street parades and celebrations. Political opponents on the Left see this, his final curtain call. But is it the end of Berlusconi? Maybe not. Although he resigned as prime minister, Berlusconi did not resign from Italian politics, which he’s dominated for the last 17 years. He still heads Italy’s most popular political party Il Popolo della Liberta. His party and coalition partners won the last parliamentary election by sizeable margins. Berlusconi is still popular among Italians in most northern regions. Some believe at 75, Berlusconi is too old to ever make a comeback in politics. But in a country where octogenarians bicycle their way through tight city streets, 90 year olds sculpt, and 100 year olds paint, Berlusconi has some time to go before the rocking chair. Berlusconi also has a weapon that all politicians envy. He’s rich, very rich. With a net worth of $6.2 billion, owner of Italy’s largest television network, Berlusconi has ample resources at his disposal to attempt a political comeback any time he wants. A Machiavellian View Italian politics are never what they seem. Take for example Berlusconi’s resignation. It may have more to do with his comeback than his fall. He may have taken a page from Machiavelli’s “The Prince” in deciding to call it quits…for now. Berlusconi knows that Italy’s debt has to be reduced either through major cuts or tax hikes. Neither is popular. Why not let an interim prime minister, Mario Monti, make the tough choices, most likely a combination of both. Berlusconi can wait a year or two before Italians in the North complain. They will gripe, as usual, that high taxes do nothing more than subsidize the South. Berlusconi can tap into his core constituency in Milan and Turin to campaign on lower taxes for everyone. Not too far fetched when you consider Berlusconi ran the same campaign to oust Romano Prodi, who also was called on to make the tough call on debt about a decade ago. Enter Monti…Now What?

Italy’s new prime minister is Mario Monti. After Berlusconi’s resignation, Monti was called by Italy’s President Giorgio Napolitano to form a coalition government and get Italy’s budget out of the red. Who is Monti? Most Americans probably have never heard of him. He was never a political celebrity in Italy compared to the likes of Silvio Berlusconi. Monti seems well-prepared for the task of revamping Italy’s economy, however, with a degree in economics from Bocconi University, a private learning institution in Milan where he once served as its president. Monti completed graduate work at Yale University under Nobel Prize winning economist James Tobin. A career in economics for Monti comes from active membership in governmental or quasi-governmental organizations. Monti epitomizes the inside player of international economics. He is a member of the board of trustees for Friends of Europe, an organization that seeks ways to manage European economics and culture. He is the former chairman of the Trilateral Commission, and a member of invitation-only economic forum Bilderberg Group. These organizations are often rumored in Europe’s café circuit as main players in global financial conspiracies. Although Monti is not popular in Italy, he is among European Union supporters and bureaucrats. He served as a European Commissioner beginning in the 1990s with responsibility for Internal Market, Financial Services and Financial Integration, Customs, and Taxation. He earned the nickname “Super Mario” among colleagues. Monti made headlines when he led an investigation into alleged monopoly practices by Microsoft in Europe. He helped to block a merger between General Electric and Honeywell in 2001. Monti’s first days as prime minister seem wholly consisted with his work experience. His appointments to head Italy’s cabinets are a who’s who of international finance and academia: There is Corrado Passera, chief executive of Italy’s biggest bank Intessa Sanpaolo, who will preside over economic development and infrastructure; Piero Gnudi, chairman of one of Italy’s biggest utility companies Enel who will head tourism and sports; Italy’s Ambassador to the United States Giulio Terzi di Sant'Agata will be the new foreign minister; Andrea Riccardi, founder of Catholic peace agency Saint’Egido, will take over international and domestic cooperation. The latter appointment leads many Italians to believe that the new political class is closely aligned with the Vatican, a makeup to the Christian Democratic party that dominated Italian politics for decades. Blame not the Italians Italy’s debt is nothing new. For almost 20 years Italy has operated under a debt-to-GDP ratio of 120 percent. That did not matter much until the 2008 financial collapse. European banks suffered huge losses and have never gotten back on solid ground. Besides real estate that sank in the United States, European banks invested heavily in Italian bonds, far more than they did in Greece, Portugal, Spain and Ireland combined. Since banks are already in a weak state, the losses from an Italian default could push them into bankruptcy. Past budget deficits were overlooked when Italy was averaging three to five percent growth annually. But Italy’s economic growth for the last decade has been paltry: less than one percent. Italy’s 1 trillion annual budgets far exceed her growth. Add to that the demands of European Union membership that does not allow Italy to govern itself economically. Italy is unable to craft policy supported by her citizenry to decrease her debt. Rather, anything that comes out of parliament has to also meet tests officiated by European Union bureaucrats, rather than Italians themselves. Most European economists and journalists, Keynesian in nature, tend to blame for Italy’s plight not government mismanagement, crony capitalism, or European Union bureaucracy, but rather Italy’s small family-owned shops, a lack of regulation and citizen thrift. Editorials from newspapers in London and Paris urge Italy to raise taxes on her citizens and crack down on the black market. These and other demands by outsiders boggle the minds of Italians. They see a plethora of small businesses because big businesses often fail. At almost 50 percent in combined personal, local, regional, sales and value added taxes, they don’t understand how they can pay more. The tax burden is so great and cumbersome that Italians increasingly evade them by shopping on the black market. They see strange a call for more regulation when Italy is considered one of the most regulated in the world. As for citizen thrift, how can you blame them? With Italy on the verge of bankruptcy, they must save for the storm to come. Debt and politics Italians feel that politics are intertwined in debt. They greet cynically the new prime minister. Mario Monti is professorial in outlook and demeanor, but he is far less charismatic and galvanizing than Silvio Berlusconi. Italians see this, his Achilles heel. Monti may not have the political talent, the engaging personality and backslapping persona vital in politics. He may fail to persuade rivaling multi-party figures to bring Italy’s budget back in black. The current crisis might serve the ambitions of rising political stars instead. Monti will not have an easy time cutting the government or an easy time raising taxes. He may not be able to do much. Thus he may not win the trust of France and Germany, not to mention thousands of bond holders who may rue the day they invested in Italy. Then it’s only a matter of time before the likes of Italy’s political heavyweights such as the Right’s Umberto Bossi or Gianfranco Fini or the Left’s Maria Bindi or Antonio Di Pietro, or a host of other prospects, make a move, demand new elections, oust Monti, and form their own governing coalition and become Italy’s prime minister.

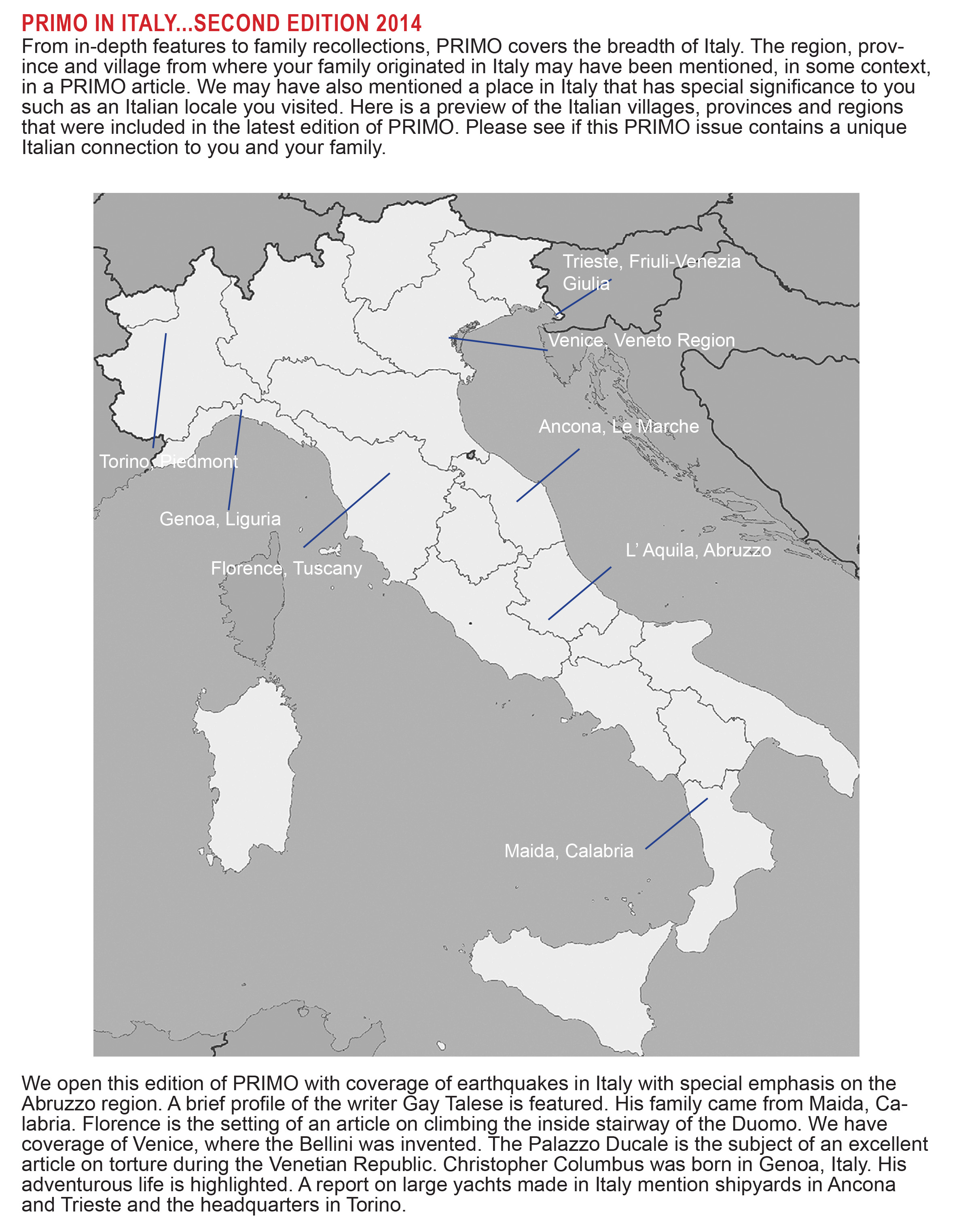

|